Artist Profile & Interview: Mizuki Nishiyama

Hapa Mag - MAY 9, 2020

By Sam Tanabe

Photo: Henry Thong

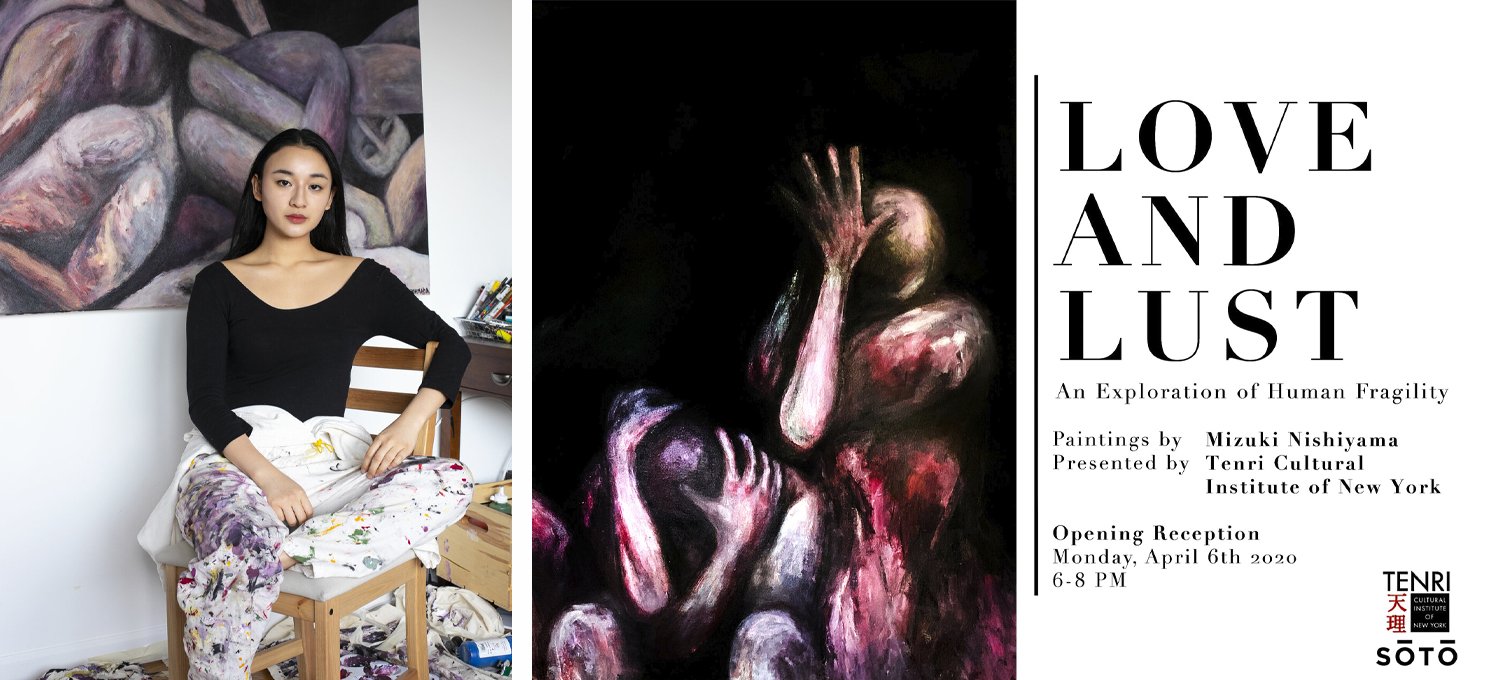

Mizuki Nishiyama is a New York-based artist known for her raw, vivid, and multifaceted paintings exploring the fragile human condition. Her work has been showcased in Hong Kong and New York City, including at Tenri Cultural Institute of New York, Hong Kong Landmark Mandarin Oriental, SuperFine! Art Fair New York, Greenpoint Gallery and more.

As a mixed-Japanese artist, Nishiyama draws inspiration from the East and West. Bridging her Hong Kong, Japanese and Italian cultural heritages, Nishiyama fuses her craft with New York’s gripping energy to establish a distinctive style representative of her unique background.

Nishiyama draws from deeply personal experiences to craft each and every artwork: her ongoing relationship with anxiety and trauma has greatly influenced her practice, and has fueled her to better understand vulnerability, fragility and the human condition. The act of painting has always been a reflective and meditative process for Nishiyama, and she finds it crucial to cope with the more tempestuous periods in her life. “Painting provides the perfect safe space for me to explore my emotions and personal circumstances within the perimeters of my canvas,” she explains. Through her work, Nishiyama challenges viewers to question the nature of the human experience and to confront their own personal vulnerabilities.

A graduate of the prestigious Parsons School of Design, Nishiyama is also currently attending Sotheby's Institute of Art in London.

Nishiyama's solo exhibitions include 脆い: An Exploration of Human Fragility (2019) at Greenpoint Gallery in New York, and An Exploration of Human Fragility: Love & Lust (2020) at the Tenri Cultural Institute in New York.

Photo Credit: Estelle Shing

Mizuki’s solo exhibition

"An Exploration of Human Fragility : Love and Lust"

has been postponed due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Tumble | Photo Credit: Frank Freeman

Funhouse | Photo Credit: Frank Freeman

Japanese Bodies | Photo Credit: Frank Freeman

Interview

Are there any specific terms you use to describe yourself? Hapa, mixed, multiracial, hāfu?

Generally, I like to introduce myself as mixed Japanese. In Japan, hāfu.

Photo Credit: Frank Freeman

Many non-Japanese people are not familiar with the concept of honne versus tatemae. Can you explain what these concepts mean to you?

I grew up with a mixture of Japanese, Hong Kong, and Italian culture. It took me a while until I became more sensitive to the subtleties of Japanese culture. Concepts like 尊敬語 “sonkeigo” (honorific or humble speech), or embracing ideas such as 内 “uchi” and 外 “soto” (inside and outside) were not introduced until a later age.

本音 “honne” is our real voice, what our heart truly wants to say. 建前 “tatemae” is the public facade. I’ll be honest, I had a bit of a struggle adopting this way of speech in the beginning. The dynamics made me feel like I wasn’t being authentic. As a woman, I need to voice my opinion loud and clear— it doesn’t mean I’m not being courteous. The sincerity was what I was most worried about. Over the years, I realize that honne and tatemae is more of a sophisticated play on words. Humans are complicated creatures, and speech is a collection of multilayered veneers. Honne and tatemae comes from a recognition that we don’t want anybody to feel shame or discomfort.

Every culture has their own version of honne and tatemae. The Japanese version simply stresses one’s ability to be aware of themselves, others, and their environment. 空気読み “kuuki yomi” (reading the air) is another layer to understanding honne and tatemae. "Air" is translucent, colourless, and odourless. Yet it is something Japanese people need to be able to detect instantly. The flow and energy changes within the speech (the air) is how one would deliver honne and tatemae within interactions. It’s all about respect and protection.

Did the intersectionality of being a mixed woman in Japan affect the type of societal repression you felt there?

Japan is an inviting society, but it is also a bubble that I felt like I was expected to “fit into.” As a mixed person, I feel like I've been initially judged on two key points: How Japanese I look and if I can speak the language fluently; picking up the subtle Japanese way of speech (e.g: honne and tatemae).

I look full Japanese, but I have a slight accent when pronouncing certain words. The lack of fluidity in my speech is usually how people know I am either mixed or perhaps grew up abroad.

Women are extremely resilient. The Japanese women I've grown up to know are extremely resilient. There are always things that could be improved upon, but I think it is important to note that the modern Japanese woman is determined, tenacious, and powerful. However, just like anywhere else, society plays a repressive role in our progression. The #KuToo Movement in Japan (high heel policy in the Japanese workforce) is a glimpse into how modern Japanese women demand to have reasonable choices, yet societal expectations still linger. I had a conversation with a Japanese woman based in New York. Just like myself, she returns to Japan frequently, and the last time she returned, she noticed a problematic advertisement. In the Tokyo subway, there was a beauty advert teaching women how to strategically apply your makeup so it is more appealing to men.

Instances like this confuse me. Perhaps it is the Japanese language again, honne and tatemae. Japanese women think and act as they please— just like anywhere else— but in Japan, society still has the main wheel to drive the premises. People let things slide as a subtle act of respect. We want to refrain from causing tremors in already set dynamics, but that also means outdated rules still govern modern times. This is an area I believe honne and tatemae should be reconsidered.

Photo Credit: Frank Freeman

What has been helpful to you in finding your own cultural identity?

Interestingly, now that I live in New York, it is also the first time I have made so many Japanese and mixed Japanese friends. Previously living in Hong Kong, I was grouped within the expat community. Perhaps it’s because everybody is so drastically different in New York, we subconsciously pick up on things that make one ほっとする “hottosuru” (feel at home). For me, it was eating Japanese food, speaking to Japanese people, and being more involved in the culture. In addition, my perception of identity shifted when I started volunteering as a teacher at a Japanese arts and education institution for kids in New York. Almost every student was mixed Japanese, and it was simply an incredible experience. The fact that there was a safe space for children just like me to interact was so heartwarming.

These kids growing up in New York are in a place where they’re introduced to so many different cultures. We remind them that they can mold their own identity. We encourage them to create their own version of what it means to be Japanese, or what it means to be a hāfu.

How has your unique cultural makeup influenced your art?

I work with the concept of human fragility, and vulnerability. Recently, I began exploring a new series inspired by Japanese ancient erotica; 春画 “Shunga”. I would like to admit that there were moments when I felt inspired by an exoticism within my own culture. I was reminded that there are so many unexplored areas of my identity, of being Japanese. I say “exoticism” asking for open mindedness— coining a Western term to let you get a glimpse of my sometimes frustrating identity struggle.

I have made peace with the fact that my identity is what I make of it. But when it slips my mind, I am placed in a situation where I begin questioning my authenticity. I become lost. However, the fascination and interest regarding my family history keeps that excitement alive. It pushes me to further educate myself and see how I can piece this together. The series “Shunga” is an expressionist rendition to the clean wood block Japanese aesthetic. I blend feverish strokes that may look unintentionally similar to post war German Expressionist works— I simply visualise the type of energy I feel as a woman and a painter onto my canvas. The intimate positions my characters are put in, showcase glimpses of the traditional style I feel haunted and inspired by. It is a play of culture, and most definitely expectations.

End of Interview

Sam Tanabe is a NYC based performer and writer for Hapa Mag. He has performed on Broadway, Off-Broadway, and regional theatres across the country. His passion for the arts has led him to fight for diversity and representation on stage. Follow this kawaii yonsei hāfu bb on social media @Tanablems.