Colorism and Classism: Keeping the Poor, Poor

Hapa Mag - AUGUST 26, 2020

By Maya Richardson

I have a complicated relationship with the sun. When I was younger, I remember the white girls I grew up around obsessing over lying outside and tanning for hours in the summer. They wanted to be sun-kissed, holding their arms up to mine after a day at the beach, pining for something close. This was confusing for me. These were the same people that would make fun of my wide nose and kinky hair — my non-Eurocentric features. The obsession with my skin tone was beyond me, but it didn’t stop my own obsession with it. I was getting this weird satisfaction from being the same color as my white friends for a few months out of the year. Me at my palest was what they liked. Soon, the sun and I sadly became much more distant friends.

In Asian countries, exposure to the sun is far from what is desired from a day at the beach. There is a well-known saying in China that goes: “A white face covers a hundred ugly things.” Tans don’t signify vacation and free leisure like they do in America. They signify low-class labor. Asian colorism and American colorism may differ in some ways, but they both have common ideologies that dark-skinned people are worth less. The skin-lightening cream business is booming, but this issue goes beyond beauty. In many Asian countries, skin color serves as an indication of socioeconomic status.

“A woman should always have fair skin,” one mask-wearing bather explained. “Otherwise people will think you’re a peasant.”

Photo by Sim Chi Yin for The New York Times

At Qingdago No.1 Beach in China, some found these masks over the top — though practically everyone was still avoiding the sun. The beach was still a land of umbrellas and tents, featuring large sun hats, surgical masks, long-sleeve shirts, and even lightweight gloves.

This fixation on fair skin isn’t about looking Eurocentric. The desire to be light is a desire to look like rich Asians, not like whites. In The Significance of Skin Color in Asian and Asian-American Communities: Initial Reflections, a Cambodian-Chinese man stated, “In the Cambodian community, [dark skin is] associated with less intelligence, laziness, working manually and lower class, and unattractiveness. Business people are the lighter-skinned ones, more intelligent, more ethical and morally superior. People want to look whiter because it’s associated with wealth and status.” (Jones, 1116).

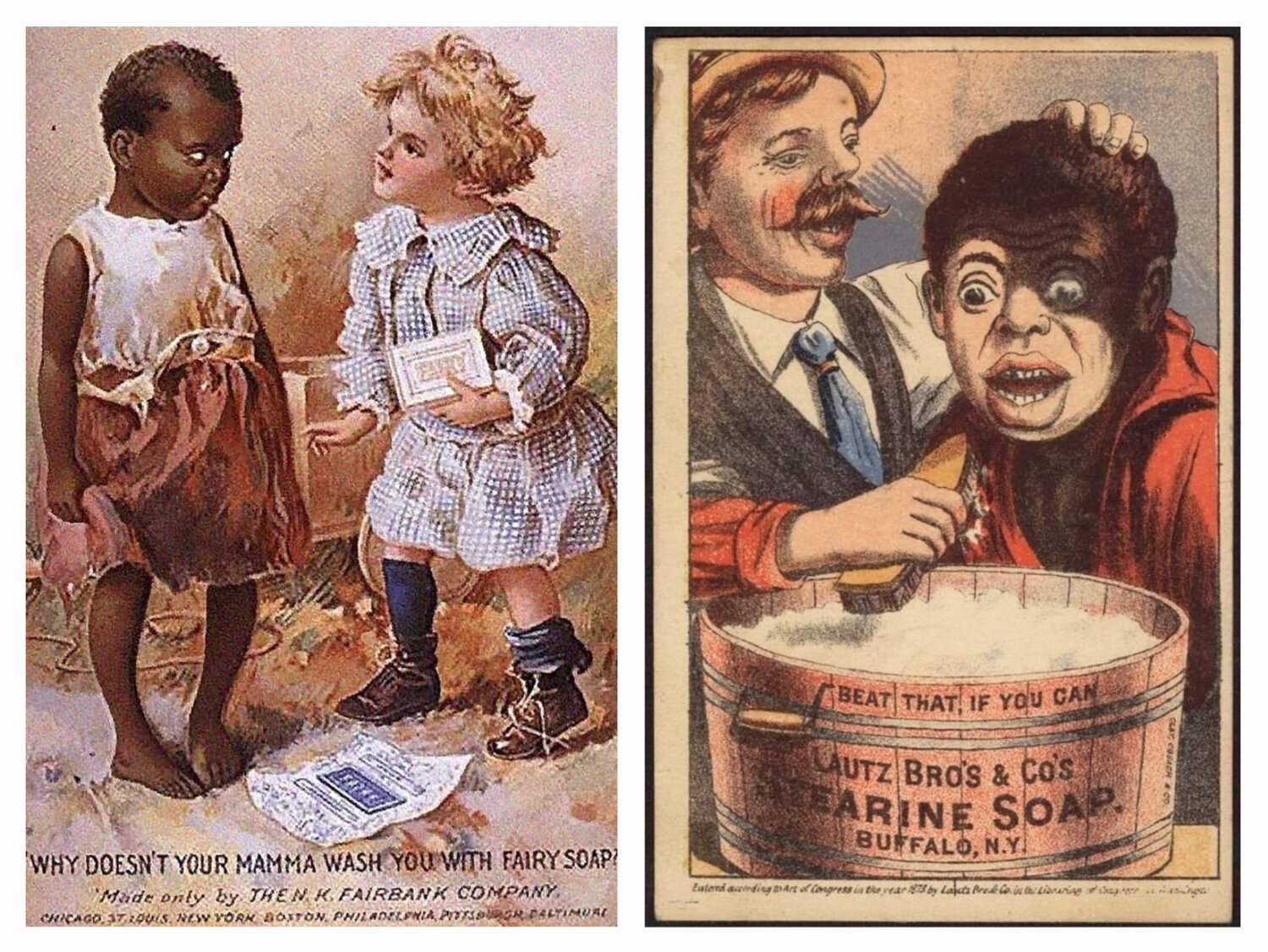

In the United States, colorism puts emphasis on beauty and the desire to look Eurocentric, and the ideas of dark equating to poor still exist, though not as outwardly obvious. Take a look at these old soap advertisements. Yes, colorism is defined as occurring within the same racial group, but the discrimination of shade has leaked outside of same-race communities into how white people perpetuate gross colorist ideologies. I wondered if colorism was the correct term to use to describe these photos because the discrimination shown isn’t happening within a Black community, but no matter what, at the end of the day, it is not light-skinned people in these photos. A light-skinned Black person’s privilege ties into their proximity to whiteness. Light-skinned people still face racism, but they have a greater chance of being hired, having more safety in healthcare situations, being given overall respect, etc., as compared to a Black person with dark skin. It’s complex. It is privilege still riddled with discrimination and pain, but nonetheless, comparatively, it is privilege. Sometimes, privilege doesn’t seem like the right word to use here. Ultimately, none of us win, but like I said, light-skinned Black people are not in these photos. They reap less shame and more praise. Although Americans obsess over perfectly tanned skin in the summertime, we are still being taught that darker than a nice “tan” equals poor equals dirty. The ideologies between Asian and American cultures may not be as wildly different as you think.

Apart from the obvious fact that the little girl on the right is insinuating that the girl on the left is dirty because of her dark skin, note the clothes they are wearing. Girl on the right has a brightly colored, sweet, and clean dress. Girl on the left is in a ragged, messy, and darker dress, not even wearing shoes. There is clear commentary being made on the socioeconomic status of the children’s families. Taking it a step further, noting the posture of the little girl on the left, her clutching her dress, a downward gaze and her feet turned in, all notes of shame. The girl on the right is open, in a more dominating and confrontational position. Our minds process and absorb all of these things at once when we see advertisements like this, whether we realize it or not.

In the next ad, a white man is literally WASHING AWAY another man’s Blackness, aggressively holding him by the back of his head in a forceful manner. The top of the barrel says “BEAT THAT, IF YOU CAN.” This insinuates that there is nothing as effective that can clean the lowest of the low, dirtiest of the dirty — this man’s Black skin. Not to mention the Blackface occurring here, but THAT, my dear friends, is for another lengthy article.

I wish I could say that ads like that don’t exist anymore, and that dark skin isn’t considered a poor quality to be washed away, but if I did I would be lying. Harmful, violent narratives like this are still well and alive. The ad on the right is from 2011 and the one on the left is from,

DRUM ROLL PLEASE…

Two thousand and seventeen. Two zero one seven.

I know.

Did I mention that as of 2020, white women still only make $0.81 for every dollar a white man makes, but Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaskan Native women only make $0.75? Or that a recent University of Georgia study showed that employers prefer light-skinned Black men to dark-skinned Black men, regardless of their qualifications? (Winters, The Impact of Colorism) Is our entire world designed to keep dark-skinned individuals behind, in every way?

I wanted to title this article “Welcome to America, where we do whatever we can to keep those already marginalized at the bottom.” But sadly, this issue exists almost everywhere and listing locations would be far too long for a clever title. I find it frightening that such different cultures carry the same shockingly, harmful narratives surrounding colorism. Apparently, there isn’t a right answer. Society not only works hard to keep the poor, poor, but based upon even basic beauty standards, it is also built to keep them feeling terrible about themselves. White supremacy capitalizes off of insecurity. Off of public shame. The more we learn, hopefully the more difficult it is to keep quiet. Society works hard, but we have to work harder.

References

Jones, Trina. The Significance of Skin Color in Asian and Asian-American Communities: Initial Reflections. 2013, www.law.uci.edu/lawreview/vol3/no4/Jones.pdf.

Levin, Dan. “Beach Essentials in China: Flip-Flops, a Towel and a Ski Mask.” The New York Times, 4 Aug. 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/08/04/world/asia/in-china-sun-protection-can-include-a-mask.html?_r=0.

Winters, Mary-Francis. “The Impact of Colorism.” The Inclusion Solution, 13 Oct. 2016, www.theinclusionsolution.me/the-impact-of-colorism/.

Mixed in America (MIA) empowers the Mixed community and heals the Mixed identity. MIA is run by two multiracial activists, Jazmine Jarvis and Meagan Kimberly Smith, looking to have a more nuanced conversation about race in America.Embracing duality is not easy. The resulting wounds are oftentimes invalidated, misunderstood, and ignored, leaving us with very few resources to assist in authentic healing. Mixed in America aims to provide these resources and facilitate spaces to remedy these complex challenges. mixedinamerica.org