Dana Tai Soon Burgess on Discovering the Dances Within Life

Mixed Asian Media - June 16, 2023

By Sunhi Willa Keller

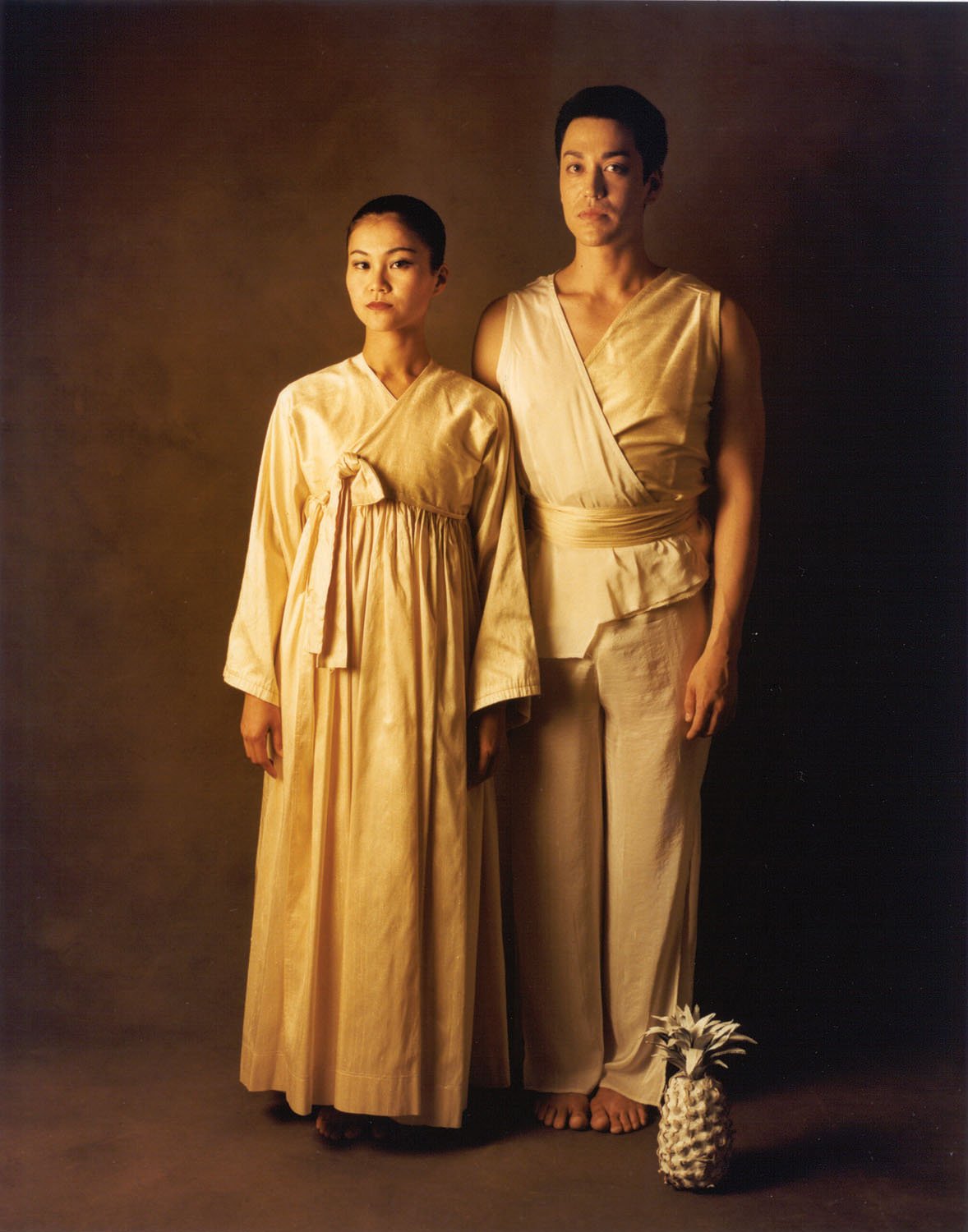

Photo Credit: Sueraya Shaheen

You know that feeling you get when you indulge in a piece of work that resonates with you so much that it fills you with the warmth of hugging a dear friend? That’s how I felt reading Korean American choreographer Dana Tai Soon Burgess’s memoir, Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly. I caught myself audibly gasping, laughing, and shedding tears throughout — reading Burgess’s words felt almost therapeutic. Being a mixed-race Korean American dancer and aspiring choreographer myself, I found a sense of home in Burgess’s story.

When I had the opportunity to talk with Dana Tai Soon Burgess about his memoir, artistic process, and advice to young artists, that feeling only blossomed. Burgess has been a leading force in the modern dance world and beyond — he holds multiple honors and awards (including the Selma Jeanne Cohen Award), the Smithsonian Institution has named him their first choreographer-in-residence, and his renowned company (Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Co.) performed for President Obama and his administration in the White House.

Embodying the vulnerability of his memoir and the grace of his choreography, Burgess was a delight to speak with.

Interview

Tell me a little bit about your background and how you got into dance and choreography.

I grew up in Santa Fe in New Mexico, and my parents are both visual artists. My father passed away a few years ago, but my mom still makes art every day. She's amazing. They moved to Santa Fe to be part of the artist community there, so that’s where I grew up. I was always searching for my own artistic medium. Like, how can I express myself because I wasn't a visual arts person like my mother? I thought, maybe I wanna do piano.

And then my parents instead of taking me to piano class, took me to a martial arts class and I met this amazing instructor Makio Nishida — he still has a school in Texas and we're in contact. I just loved moving and I loved the discipline and I loved the meditation, just all of it.

Then one day my dad said, “Why don't you take a [dance] class with your friend Salome?” So I took a dance class and that was it for me.

With the first class, I just knew this is what I have to do because it was this perfect synergy of movement like martial arts, but then it had this whole creative side that I was looking for. And that's really how I started. It was this kind of serendipitous moment of connecting that Asian movement side of martial arts to dance and creativity.

Photo Credit: Mary Noble Ours

Amazing. You mentioned how both your parents were artists. How did that influence your own artistry?

I grew up literally just seeing the creative process every single day and seeing it unfold from start to finish. And also seeing the frustrations and the trials and the tribulations of making art. I think back to it every time I'm in the studio, because I realize that I look at the creation of a dance and the studio sort of as this canvas and the dancers are kind of like brushstrokes for me, and I think of the proscenium that way also. That relationship of seeing the creative process and also just knowing what an artist's life is like really, I think informs me still to this day.

There were [also] these really interesting interactions as a young child with these amazing artists. And all of those conversations, I think, still really influence me.

I'm really captivated by the way that you view all mediums of art in relation to dance. You seem to be in constant conversation with artwork in general, even work created centuries before your own. How do you incorporate different mediums in your choreography?

I think that art for me becomes this entry point through which I can ask a lot of questions and I can learn more about a time period that an artist lived in, what their social and even political context was. Then I’d research, finding out more about their personal stories, not just the historical context.

So that journey for me illuminates the artwork. And then within that, I find all these multiple stories, which are great. Really great entry points to begin to choreograph.

Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company, Hyphen (2012). Photo Credit: Mary Noble Ours

As a dancer myself, I really admire the way you speak about your own company in your memoir — it's really clear that the dancers are like a family to you. Even the way that you talk about everyone that you've come in contact with — from collaborators to people that you've just spoken with — it’s clear how much inspiration you gather from the people around you. Could you tell me a little bit more about the importance of these people to your artistic process?

A few years ago I had this realization that everyone that was in the studio was somehow part of this patterning of archetypes that I seem to constantly recreate. We're in our 30th anniversary season now, so we've had so many generations of dancers move through the company, and I realized there's always someone who reminds me of this person when I was growing up. [For example], there's somebody that reminds me of my mom, or there's somebody that reminds me of a cousin, or of the sister I never had and always wanted. I realize that as a choreographer, you sort of create this world and the dancers inhabit that world and become these characters that you can mold work on.

And the same thing happens with collaborators. It's like these relationships with a certain production designer, for instance, that I might have long-term [relationships with] are very related to how I view their aesthetic and how it fits in with my aesthetic, whether we can get along and if we speak the same language. It's almost like an immediate attraction to the artwork and the person.

I love that. I'm really curious about how your Asian American background plays into the development of your work even today. In your memoir, you talk about your piece “Hyphen,” which really feels like an exploration of your identity. Could you talk about how you started using choreography to explore your Korean culture?

I'm a firm believer that really we choreograph about what we know, right? I just started choreographing about family history and the feelings of being in between worlds, [about] being that kind of hyphenated part of Asian and American and exploring that with my friends who were also Asian American.

We've always had Korean American dancers in the company and it was a natural journey to try and better understand the self. Where did I come from? Who were my ancestors? What were their journeys? Because those stories weren't prevalent in the field. They probably still aren't that prevalent in the field, the Asian American diaspora, and experience. So that became really important to me. Along the way, even as I explored other stories about a sense of belonging or trying to find a place to call home in America, it was always through an Asian American lens; [of a] Korean American trying to fit in. I think it's a really great lens because it helps me find the universal message that connects us all. And I really do think that that message is that we all long for a safe place where we can dream. Where we can create and be ourselves in a community that accepts us.

Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company performs The Foster Suite at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Photo Credit: Jeff Malet

Do you have any advice for any young creators making artwork?

I think it goes back to my thoughts on [being] a choreographer: that a choreographer probably makes their most successful work by beginning with stories that they personally know, or emotions that they're personally feeling. For an emerging choreographer, I would say to focus on your uniqueness because choreographers build a name and a repertoire around their uniqueness. The sooner that one can be courageous enough to just embrace that and delve deeply into [questions like] Who am I? How do I move? How do I tell stories through movement?

I really think it's the groundbreaking act of just following one's own aesthetic. And that's hard because sometimes the field isn't ready to embrace that yet or doesn't understand it, so a young artist might have to go through 10 years, 15 years of producing their work or even self-producing their work in order for people to acknowledge it and for an audience to be built. It just takes time. But it's worth it.

And it was really lovely to read your journey about finding your place in the choreographic world.

Oh, thanks. I think so much of it was full of serendipity and that's another thing I would say to young choreographers: Don't forget serendipity because it's there for us.

There are these epiphany moments. There are these moments where people discover your work and want to support your work. Those moments happen. And ultimately what's going to make that career is consistency in art-making.

Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company, Silhouettes (2018). Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Photo Credit: Jeff Malet

Speaking of art-making, what do you have planned coming up?

I'm super excited about several projects. We just completed a project about the transcendental painting group of New Mexico. They're some of the earliest modern paintings of America, really. They're not that long after Kandinsky and they loved Kandinsky's work. So that was really fun to do because it was visual, it was colored, it was action, and with live piano.

I [also] have a new commission coming up for the Kreeger Museum, which is based on Joan Miró works in the collection, and that's super exciting because there's this abstraction that allows for a certain freedom of movement and form to occur [between] different relationships in this space.

And then I have a really big project that I'm super excited about. I'll be an impact partner in residence at the Kennedy Center starting in the fall. I'm working on a project called Seeds of Toil, three Asian American stories of resistance and resilience. And it's these three stories that I think will help people understand the diversity of the Asian American community and also this layer of systemic racism built into the land.

One section will be about plantation workers in Hawaii [from] the last century, like my family. Another story is about Japanese American agriculturalists who were living in California and the impact of Japanese internment. And the third is the relationship [between] Filipino agricultural workers and Mexican agricultural migrant workers and how they worked together in order to change the working conditions of the workers themselves.

For me, these are three interesting stories that are about land and about relationship to land. What's fascinating, prior to World War II, the majority of agriculturalists in California were Asian American. And today it's less than 1%. So there you can see where there are these socio and political impacts on land itself.

That's kind of the journey I'm on right now: investigating those three moments in American history and how to best represent those in a trilogy.

I got chills when you were talking because even though the stories that you're telling are different segments in American history, it also feels so relevant today, especially with climate change and all of our discussions about land and who owns it, and all of the history within it. It's really amazing what you're doing.

Yeah, and you know what's wild too, there's a whole new generation of Asian American organic farmers that are making a whole resurgence in the field right now, and that's really exciting.

Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company, Tracings (2003). Photo Credit: Mary Noble Ours

That's so interesting. I really look forward to your next season, and hopefully, I can see some of your work in person one day.

Oh, I hope so. That would be so great.

End of Interview

Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly is available for purchase online or at your local bookstores. Click here for a list of DTSBDC’s upcoming performances.

Sunhi Willa Keller was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawai’i, surrounded by two wonderful parents, a brilliant big sister, and many, many feisty dogs. She holds a BFA in Dance and a BA in Art History from New York University and she recently received her MA from London Contemporary Dance School. When she’s not wiggling about a dance studio, she enjoys writing rom-coms, completing jigsaw puzzles, and munching on hot stone bibimbap.