The Presentation of Multiculturalism in the World of Avatar: The Last Airbender

Hapa Mag - SEPTEMBER 16, 2020

By Lauren Lola

The following contains spoilers from Avatar: The Last Airbender, The Legend of Korra, The Promise trilogy by Gene Luen Yang, and the Kyoshi duology by F.C. Yee.

Fifteen years following its debut on Nickelodeon, the beloved animated series, Avatar: The Last Airbender, is experiencing a renaissance after returning to Netflix back in May. Centered in a world where people can manipulate/bend one of the elements from the four nations — water, earth, fire, air — Avatar Aang, the sole person who can bend all four elements, must master all of them in order to end the Hundred Year War.

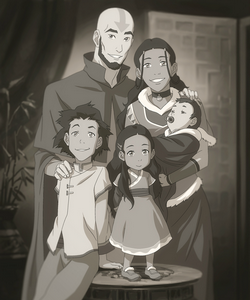

Aang, Katara, and Their Children

Since its return, audiences who grew up with the series — myself included — have been aboard the nostalgia train, whereas new audiences are experiencing the fantastic world-building, character development, and well-written story for the first time. Although originally targeted for kids, the show touches on subjects ranging from sexism to genocide, morality, and destiny. The same applies for the expanded material as well; from its spin-off series, The Legend of Korra, to the graphic novels published by Dark Horse Comics. However, there is one topic explored more so in the expanded material that means a lot for me to see: multiculturalism.

The depiction of mixed relationships isn’t anything new for the original series. Sokka (Water Tribe) is in a relationship with Suki (Earth Kingdom) for the latter half of the series, whereas Aang (Air Nomad) has a crush on Katara (Water Tribe) for a majority of the series, before they too get together in the very last scene of the series finale. However, the subject matter wasn’t explored as in-depth until 2012 when the first trilogy of the graphic novels, The Promise, was released.

Written by Gene Luen Yang and illustrated by Studio Gurihiru, the story is set one year following the end of the original series. Aang and Fire Lord Zuko are leading an effort to remove the Fire Nation colonies from the Earth Kingdom. However, they run into a problem with the town of Yu Dao, where families have been living there for generations and are made up of both Fire Nation and Earth Kingdom citizens.

Mako and Bolin

The idea of belonging to more than one nation is explored particularly in the character of Kori Morishita, an earthbender who’s a citizen of the Fire Nation and daughter of Yu Dao’s mayor. She embodies the idea of this brave new world more than anyone else. When her boyfriend, Sneers, who’s originally in favor of the removal of Fire Nation citizens, tells her to choose a side, Kori gives a response that is beyond impactful: “Choose, choose choose! All my life, people have been asking me to choose! I am an earthbender and a Fire Nation citizen, and I live in Yu Dao! That’s what I choose!”

This first trilogy, and that line in particular, really resonated with me personally as a mixed-race person. To go your life not fitting neatly into one box or having others try and define your identity for you can be excruciatingly frustrating. The fact that another war nearly breaks out over this is wild to comprehend — and this is in a world where creatures like platypus bears and sabertooth moose lions exist! It’s interesting that Aang is the one on the opposing side, despite previously learning from Guru Pathik that the people of the four nations and elements aren’t as divided as they otherwise live to be.

Although The Promise trilogy isn’t the only time there are characters from multicultural families, this is the only time in the canon so far where it’s explored as in-depth as it is. In The Legend of Korra, two of the main characters, Mako and Bolin, are also children of an Earth Kingdom and Fire Nation family. Not a lot of focus is placed on their multicultural background, as more focus was shown on their struggle to survive after being orphaned when they were very young. However, nuance to their multiculturalism is expressed in their bending. Mako, a firebender, is capable of bending the sub-element of lightning, and later in Book 3, Bolin, an earthbender, finds out that he too has the ability to bend a sub-element: lava. The latter seems appropriate for someone who has Fire Nation lineage.

Mako Bending Lightning

Bolin Bending Lava

Another main character, Tenzin, an airbender, also comes from a multicultural family, as the youngest son of Aang and Katara. But it’s here where I feel that the presentation of being from a multicultural background falls short. Tenzin is of both Air Nomad and Water Tribe lineage, but you wouldn’t know it from his devotion to keeping the Air Nation alive. While he has an immense amount of pressure on him to keep alive a culture that was nearly wiped out over a century before he was born, I still think it would have been nice to see how his Water Tribe lineage plays a role in his life.

Same can be said for his older siblings: Kya, a waterbender, and Bumi, a non-bender who later becomes an airbender in Book 3. However, Kya seems to be pretty in tune with her Air Nomad lineage through her knowledge about its history, as well as her profession as a meditation instructor.

Bumi and Kya Teasing Tenzin

Their appearances don’t seem to reflect their mixed heritage either. Katara and Sokka stand out to me as the first animated characters with similar skin complexions as mine as main characters of a TV series. I would like to have seen more physical attributes from Katara’s Water Tribe lineage in not just Kya, but maybe also in Aang and Katara’s airbending grandchildren. The clothing they wear also plays into aligning more with the element they bend, for not once have I seen Tenzin wear any Water Tribe get-up, nor have I seen Kya in Air Nomad clothing.

Speaking of bending, it seems that for the children of the Avatar, I would like to think that they would have embraced the possibility of incorporating bending techniques from elements other than their native one. Already, both airbending and waterbending include circular movements, so it wouldn’t have been too hard to incorporate influences from them. Lack of nuances like that make Iroh look extremely ahead of his time when, in Book 2 of Avatar: The Last Airbender, he teaches Zuko how to redirect lightning with a technique he invented from studying the style of the waterbenders. As he conveys to him, “It is important to draw wisdom from many different places. If you take it from only one place, it becomes rigid and stale. Understanding others, the other elements, and the other nations, will help you become whole.”

If you wanted to take it a step further as far as common ground goes between the four styles of bending, just look at the martial arts they’re based off of. Earthbending and firebending are both based on different styles of Kung Fu (Hung Gar and Northern Shaolin respectively). As for airbending and waterbending, they are based off of Baguazhang and Tai Chi. They’re both internal martial arts; where the emphasis is less on flashy movements and more on spiritual and mental stability. It’s also worth noting that all these martial arts originated in China.

Kya, Bumi, and Tenzin

Much like in our own world, the development and presentation of multiculturalism in the world of Avatar is a gradual process; slow to be seen and accepted with time. Aside from Aang’s initial opposition to letting Yu Dao remain as it is, this idea of cross-culturalism is also evident in The Rise of Kyoshi by F.C. Yee, when Kyoshi — one of Aang’s predecessors — is revealed to be of both Earth Kingdom and Air Nomad lineage. Orphaned at a young age, it makes her desire to connect with Avatar Yangchen (an Air Nomad) in Yee’s recently released The Shadow of Kyoshi all the more understandable.

Bottom line, the subject of multiculturalism in the Avatar world is unabashedly present throughout, but could use some work. However, in the stories that really focus on not belonging in one tidy box, the characters and this world become all the more real and relatable for me. Now that Avatar: The Last Airbender is experiencing a revival, my hope is that it will open up even more avenues for stories to be told, where multicultural characters can be explored and portrayed with even more nuance — or, echoing Iroh and Guru Pathik, more wholeness — than before.

Lauren Lola is a San Francisco Bay Area-based author, freelance writer, playwright, and screenwriter. She is the author of the novels, An Absolute Mind and A Moment’s Worth. She has written plays that have been produced at Bindlestiff Studio in San Francisco, and in 2020, she made her screenwriting debut with the short film, Breath of Writing, from Asiatic Productions. Aside from Hapa Mag, Lauren has also had writing featured on The Nerds of Color, CAAMedia, PBS, YOMYOMF, and other outlets and publications.

You can find Lauren on Twitter and Instagram @akolaurenlola and on her website, www.lolabythebay.wordpress.com.