Day of Remembrance Stories

Block Print by Naomi Takata Shepherd, carved and printed by hand on Day of Remembrance to honor the flow between every family’s past, present, and future generations.

Photo credit: Glen Cheriton

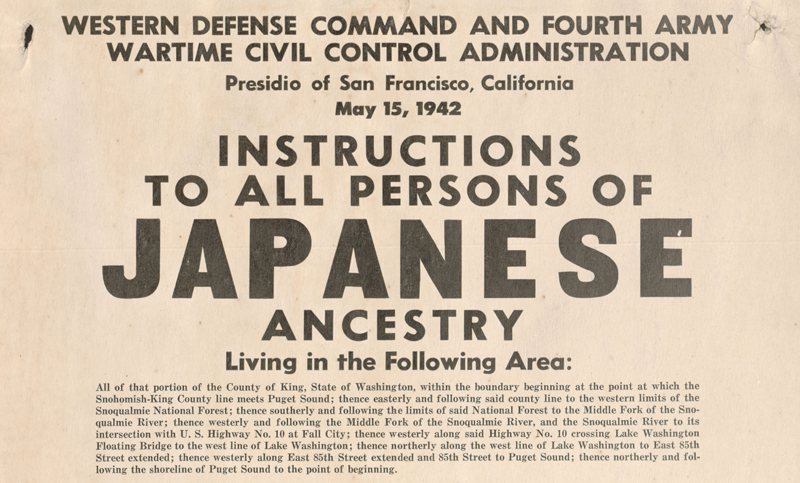

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the internment of tens of thousands of American citizens of Japanese ancestry and resident aliens from Japan alike. February 19th is now recognized at the Day of Remembrance (D.O.R.) to commemorate Japanese-American Internment so that we do not forget.

We had our Japanese-American Hapa Mag writers (plus guest writer Troy Iwata) collaborate to express their thoughts, sentiments, or experiences with D.O.R. and internment.

ALEX CHESTER

あれっくすーちゃん

I have been trying to figure out how to even start this piece. Most people don’t realize that Japanese-Americans were interned in “camps” after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor during WWII.

I can remember briefly and I mean briefly touching on this in 5th grade. I remember it being a tiny ass blurb in our history books. Nothing remarkable about it.

Trying to find out about my family in the camps hasn’t been easy. I knew my grandfather Tad Iwata was in the 442nd regiment and fought for his country the United States. To be perfectly honest, he didn’t have much of a choice. You were either interned or you fought.

Here is what I do know. My great-grandfather Tatsugoro Iwata was an officer of a social Japanese club. Right before the mandatory evacuation took place he was arrested and taken away.

No one knew what happened to him and his family thought him dead, until one day he appeared at the camps.

The rest of the Iwata family was first taken to the Santa Anita Race Track. My family likes to joke that they were kept in the famous racehorse Sea Biscuit’s stall. From there they were sent via train to the Internment Camp in Rohwer, AK.

My grandfather Tad eventually joined the army and was placed in the 100th Battalion, 442nd Infantry Division. They consisted of Japanese-Americans from Hawaii and the Mainland. My dad recently sent me a comic book about this specific division called Journey of Heroes - The Story of the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Tad always said he was lucky to never have been in the front line. Instead, he procured supplies for his battalion and regiment.

My grandfather passed away several years ago and I regret never asking him about that time in his life. My grandmother won’t talk about it. She went to high school and graduated while interned in Poston, AZ.

I know there are stories about the camps that many of us will never hear. I recently found out that there were camps in Mexico and Canada. Who knew? I hope that history will never repeat itself. The atrocities my family and many, many others went through should never have happened. It really is up to us to remember for those that won’t and those that have passed away. It is up to us to make sure this never ever happens again.

Sam Tanabe

サムーちゃん

Being half-Japanese I had heard of the internment camps when I was younger. They were mentioned briefly in my school textbooks, but it is never something I ever talked about with my dad or grandparents. My Japanese family was living in Hawaii at the time of Pearl Harbor and no immediate family member of mine was interned. It wasn’t until I joined the Broadway company of Allegiance that I really began to research the Japanese internment camps. I began to ask my obaachan (grandma) questions to learn more. It turns out she knows many Japanese-Americans who faces internment, and I learned that I even have family that fought in the 442.

Allegiance is a musical based on George Takei’s personal experience in the camps as a child. The story follows a Japanese-American family that is forced from their home and placed in Heart Mountain after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Working on this piece of theatre, I got to learned many stories from internees through documentaries, personal recollections, and books. One of my favorite books from all of this research is Colors of Confinement, which contains color photographs from inside Heart Mountain.

Lea Salonga, George Takei, Telly Leung, and Michael K. Lee in the Allegiance. In this scene, the uprooted family has just arrived at Heart Mountain Internment Camp

Watching Allegiance every night for several months and living in this period of unjust American history night after night, I felt more connected to the plight of the Japanese-American community. It is heartbreaking to think about these internees torn between the decision to comply with the decisions made by the government or stand up for their rights as humans and American citizens. One line from the show really gave me perspective into the anguish these people faced. After these west-coast families were ripped from their homes, had their businesses and property seized, and were placed into confinement, the character of Mike Masaoka states, “We leave without bitterness. For it is patriotic to make this sacrifice. Let this relocation be our contribution to the war effort.”

Were all of these people proud to "do their part?" American citizens of other backgrounds didn’t have to contribute in this way.

This past November I was in Hawaii performing in Allegiance, honoring the brave men who fought in the 442nd and 100th Infantry Battalion. Afterwards a Japanese woman in her 90’s came up to speak to everyone. She was crying as she begged everyone not to forget the Muslim community in America as they face an all too familiar prejudice today. It is important to remember the internment camps, to remember Executive Order 9066, and to not let history repeat itself.

Naomi Takata Shepherd

なおみーちゃん

Family stories and history are an ephemeral thing; they’re often hard to pin down and are told fleetingly, spontaneously, after a game of cards around the dinner table, or on a cousin’s front porch when goodbyes are forgotten and talk begins of what happened or may have happened and speculation about the details we’ll never quite know. At least that’s how it’s always been with my family.

My initial encounters with stories of World War II, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the U.S. government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans were comments made in passing, like the time I told my mom I had been assigned President Truman to make a twenty-minute PowerPoint about, and her reply was something like, “Great, the Japanese kid gets to research the president who dropped the bombs.” Before that point, as early as fourth grade, I was searching for stories that I suppose I thought would help me connect with a shared generational history that I somehow intuitively knew informed my identity, whether my family talked about it or not. I stumbled upon books by Yoshiko Uchida, I read Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, and was deeply touched and shaken while reading When the Emperor Was Divine in high school.

It wasn’t until I was fourteen or so that my grandparents and older relatives began to talk more about their and their families’ experiences involving World War II, and over the years, new anecdotes and stories have spun out to form a still incomplete web. I wish it were more complete, and I hope someday it will be, but I know that some of our family’s history is lost for good. My closest relative to be interned was my great-grandfather, Yoichi Takata, who had immigrated to the U.S. illegally. He worked as a farmer all over California, and during World War II, he along with many relatives of mine were forced into internment. We believe that my great-grandfather was interned at Tule Lake, but we don’t know of any documentation to back that up; there is a chance he was using another name at the time and that’s why there aren’t records of where he was incarcerated. My great-grandfather had sent his wife and three children, including my grandfather Isamu, back to Japan so that his children could be educated there; they weren’t able to return to U.S. until after the war. During that time, my middle school-aged grandfather, was forced into the Japanese army to prove his loyalty and was constantly put into situations that would get him killed because he was American-born. However, if he had not endured, he would never have become a translator for the U.S. military after the war, which was how he met my grandmother, Momoko, who was working as help to an American officer’s wife at the time.

Once, my grandfather was approached by someone, who had a similar story, to co-write a book about their experiences, but my grandfather turned him away. If I had been old enough to understand the significance of this, I would have asked my grandfather to participate, to write his story and his family’s story down for us and future generations. Even today, these stories hold significance and relevance to America as racism and discrimination continue to hold center-stage in our nation’s politics. I’m glad for Day of Remembrance because it is a chance for us to talk about our shared histories as Japanese Americans. For those of us who still have living relatives who were interned or lived through World War II, I hope we can find the courage to continue asking our relatives to tell their stories. My grandfather passed away in 2015, but I’ll never forget what it meant to have him tell us about his life after whooping us at yet another round of canasta.

Troy Iwata

トロイーちゃん

My grandpa never spoke to me or my brother. We were never allowed to participate in family functions, weren't allowed in pictures. At Christmas he’d make us sit in the corner while the rest of the grandkids opened their presents from him. As children it was easy for us to ignore, we’d just play with each other. It became more apparent as time passed, our cousins are full Japanese, we’re half white. Sometimes I couldn’t help but think that whenever my grandpa saw me walk into his house, he just saw the man who forced him to leave it.

Dr. Richard Iwata (my grandpa) teaching students at the Tule Lake Japanese Internment Camp 1942-1945

I didn’t know there were “camps” in America until I was 12. My dad casually mentioned it while we were on our way to a ski resort. We had just passed a previous “campsite” on the highway. There was a insignificant-looking building called The Manzanar Japanese Internment Camp Museum. We were in the middle of nowhere; hard, dry, dusty land surrounded by sharp mountains. I didn’t talk much for the rest of the drive. When I got back to school I asked my teachers about it, none of them were able to tell me anything. I went to public school, but still. No one in my life ever mentioned the “camps” my grandparents were forced into, no one except for my dad, every once in a while, flippantly.

Some time after high school, on the ride home from our ski trip, my brother and I decided to stop at the museum. We barely made it before closing. The grounds were deathly quiet, the air was calm but biting. I couldn't help but think about the millions of families who speed past this place everyday, downright unaware of what it was used for. The inside of the museum was beautiful; clean, warm, organized. They had managed to both accurately capture the injustices people endured as well as showcase how the Japanese made the best of a sh*tty situation. They kept their morals and bonds, and most importantly their loyalty and hope. My grandpa never came around, his disownment lasted until his death. I’m not angry and I don’t blame him for anything. He’s a victim of treating me the exact way his country treated his people.

Melissa Slaughter

りさーちゃん

In high school, I actively avoided learning about World War II. I knew it was bad for the Japanese-Americans, and I knew that someone would whisper “Pearl Harbor was your fault” in my ear. The classroom taunting was enough for me to ignore the fact that I never actually learned about Japanese concentration camps. Like most Japanese-American families, my family was directly affected and yet we never talked about it. There were small talks in my family about what happened. My brother and I knew that our family was in Hawaii and wasn’t interned, but they were homeless, kicked out of their home by the U.S. Army for being too close to the base. They only had one piece of furniture for a 10 person family: a baby’s carseat.

My nuclear family lives far from my Hawaiian-based family, so I’ve never gotten to directly talk to them about their experiences. My mother and I have talked; my late Uncle Frank and I had a phone call once, but it wasn’t until I did the play Hotel On the Corner of Bitter and Sweet (by fellow Hapa Jamie Ford) that I learned how an event two generations ago affected me. I’ve always been fiercely proud of my ancestry, and very sensitive to racial micro-aggressions. I’ve come to believe in inter-generational trauma; that WWII affected not only my family at the time, but also that it beat it’s effects into my own DNA. Understanding the narrative of Japanese Internment, seeing it’s history play out in shows like Allegiance or Hold These Truths, has helped me come to terms with my relationship with my own racial makeup, as well as given me a language to discuss the emotional trauma of war, racial politics, and history.

For the past four years, I go around the country teaching elementary and high school students about Japanese Internment. Each year, it gets harder and harder. When I started in 2014, there wasn’t the fear that internment could repeat itself. 2016’s fear-mongering presidential campaigns and 2017’s Muslim Ban changed that. Sometimes, I think about what my grandfather would say. I wish he was here to ask. But instead of mourning his lost, I'll keep speaking up in his memory.

If you'd like to know more, listen to the podcast Order 9066, produced by American Public Media and the Smithsonian National History Museum of American History.

*This isn't an ad. We just highly recommend this podcast. a lot.

If you have your own family internment, share it with us @Thehapamag with #hapamag9066.

We had our Japanese-American writers collaborate to express their thoughts, sentiments, or experiences with D.O.R. and Japanese Internment.